I recently joined the USV team and as many investors and founders, I have been a long-time reader of this platform. So, I’m honored to be writing here! For my first posts, I’m writing about something related to my career before USV: investing in emerging markets. I’m exploring it in relation to one of my focus areas at USV, climate. We have already made investments from our climate fund in Latin America, North Africa, and India. And we are excited to make more. In this post, the first of two, I summarize some of the reasons for accelerating climate investments in emerging markets. In the second part which will be published in a few weeks, I will highlight some of the areas we are researching at USV which include cooling, fintech and digitalization for the energy sector, transportation, and nature-based carbon removal solutions.

As someone from the Middle East, who also lived in East Africa and Central Asia, I know that “developing countries” is too broad of a label. To narrow it down, we’re focusing on developing countries that share similar climate-relevant characteristics: middle and lower to middle-income levels, rising urban populations, growing electricity and cooling needs, and perceived political risk that inhibits investments. We are casting a wide net for this initial exploration and plan to dive deep into some regions in the future.

Emerging economies have contributed the least to the climate crisis. Yet, many of them have limited capacity to manage its adverse effects. If climate change continues on its current path, the world will lose 10%-14% of total economic value by mid-century. This loss is due to physical risks such as extreme weather events and market risks like large shifts in asset values and higher costs of doing business. This GDP reduction will be experienced by most nations to varying degrees. Some economies in Southeast Asia and Latin America run the risk of losing economic output totaling more than seven times their 2019 GDP by 2050. Some equatorial zones such as Ghana are projected to experience 160 additional deaths per 100,000 residents as a result of the already high temperatures becoming increasingly dangerous. On the other hand, many developed economies in the northern hemisphere are the least vulnerable to climate change’s overall effects. They are both less exposed to the hazards and have greater resources to respond.

Figure 1- Global temperature rises impact on GDP by mid-century

Climate investing in developing countries is not only about preventing catastrophic losses and events – humanity’s most significant challenge! It also represents an opportunity that is waiting to be pursued (more about that in the second part). There are relatively few investors who are paying attention to the potential opportunity in emerging markets. For the past 12 months, climate tech funding reached $84.8bn. Startups in developing countries accounted for only 4% of that. This low figure might be the result of perceived risks and challenges such as political instability and lack of key infrastructure in emerging markets. However, this is not the whole story. There are many other market dynamics and favorable factors that can balance some of these risks and make investing in developing countries attractive today. Below are just a few of them:

Figure 2 – Breakdown of investment by startup region

Ability to leapfrog over expensive infrastructures and directly adopt proven technologies

The concept of leapfrogging technology in developing nations is not new. A well-known example is Africa directly adopting mobile telephony and leapfrogging over expensive landline infrastructure. African countries were able to benefit from dependable, low-cost telecommunications technology despite having limited capacity for such extensive investment in R&D. The same may be said about many of the sustainable and climate solutions that exist today. Founders in some developing countries can take advantage of advanced and mature climate-related technologies without contributing to the high R&D costs. This frees up capital for investment into implementation and scaling strategies.

One industry that will see significant leapfrogging in the next decade is energy. Traditional centralized electrification requires significant upfront infrastructure investments in building out an electric grid in order to take advantage of economies of scale at large coal and natural gas generation facilities. As a result, centralized power systems are either unreliable or have yet to reach a significant portion of the population in lower-income countries. However, centralized power systems are no longer the only way to access energy. Due to plummeting renewable energy prices and the faster deployment of decentralized power generation systems, the opportunity for developing countries to bypass traditional energy sources and centralized systems and move to off-grid and microgrid solutions has never been more attractive.

Another sector to watch out for is transportation, jumping from a system dominated by internal combustion engines and personal vehicle ownership to a system that is shared, electric, and connected.

Outsized potential for environmental, social, and financial returns:

The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated that marginalized groups often lack access to the services, resources, and information they need to mitigate and overcome crises. The climate crisis is no different; in fact, it is probably orders of magnitude worse. Climate action has often been perceived to come at the cost of other goals such as economic growth and inequality reduction. This does not have to be the case. Evidence shows that climate actions can result in multiple positive co-benefits. These benefits include reduction in local air pollution and acid rain, creation of green jobs, improvement of biodiversity, and increased energy and water security. Studies show that adequate climate actions can create more than 65 million new low-carbon jobs and prevent 700,000 premature deaths.

Availability of financial instruments to de-risk investments:

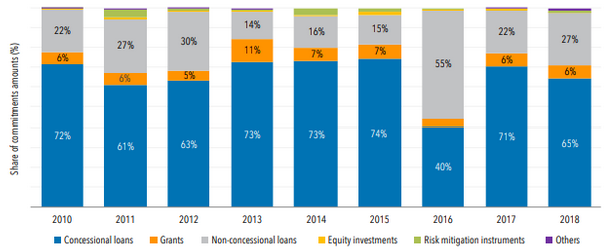

The international development community has recently stepped up and deployed various mechanisms to minimize the gap between the scale of investment needed in the climate space and the limited resources available. In 2018, development finance institutions (DFIs) helped finance over 70% of all energy investments in developing countries. These efforts are not meant to close the financing gap entirely. Instead, the intention is to use them to unlock further capital. This can happen by pairing concessional capital with commercial investments to improve the risk-return profile of an otherwise risky opportunity. Below are some examples of the financing instruments that are being deployed today:

- Concessional capital that provides funding on below-market terms within the capital structure. The goal is to lower the overall capital cost or provide an additional layer of protection to private investors.

- Credit enhancement through guarantees or insurance on below-market terms

- Grant-funded technical assistance facility that can be utilized pre- or post-investment to strengthen commercial viability and developmental impact

We have been in touch with several institutions such as the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC), the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), and the International Finance Corporations (IFC). The resources and capital they offer are especially helpful for investors new to climate, emerging markets, or both.

Figure 3 – Share of annual commitment in the energy sector by financial instrument

In the next post, we’ll share more about specific themes and opportunities we’re looking at. If you are researching, investing, or growing a climate-related company in emerging markets, we’d love to meet you and learn more. Please reach out to me at mona@usv.com.